Take Them Back Home and Let’s Start Out New: Johnny Shines, Mable Hillery, and the Revival Stage

Sophie Abramowitz, David Beal, and Parker Fishel

This previously unpublished article uses the release of Hotter Than a Bulldog Spitting in a Polecat’s Eye: Mable Hillery + Johnny Shines Live 1975 (AMP-001) as a springboard to explore Hillery and Shines as performers, educators, and activists who deftly navigated complex social, political, and historical terrain in their wondrous presentations of the blues. More info on the limited edition LP is available here.

1

On April 11 and 12, 1975, the University of Miami in Florida hosted the fourth and final Miami Blues Festival. First organized by journalism student Jim Fishel[1] and his older brother John in 1972, the annual festival gained a solid reputation, drawing an audience of enthusiastic predominantly-white college students, off-duty musicians, die-hard blues fans, and last-minute walk-ins. With bills that reflected the rich diversity of the music, the Miami festivals were intended to compensate artists fairly, to reunite musicians otherwise unable to see each other, and to “turn people on” to the music. Despite being held at a university and attended mostly by students, the concerts were “not like a classroom,” Jim noted. Rather, they were a spirited combination of music, storytelling, and explanation. “My belief,” said Jim, “was that college was to expose people to different things.”[2]

Of the performances on the Miami stage,[3] a 1975 collaboration between guitarist Johnny Shines and singer Mable Hillery stands out. Shines had performed previously at the 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festival and the 1972 Miami Blues Festival, and had a good working relationship with the Fishels. So when Shines mentioned the obscure blues singer Mable Hillery and offered to accompany her, the brothers booked Hillery on his recommendation alone.

John Fishel, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Eddie Baccus, Jim Fishel, Mable Hillery, Johnny Shines, and Snapper Mitchum at the 1975 Miami Blues Festival

The story of Shines and Hillery’s performance at the Miami Blues Festival is part of a larger story of black artists performing the “traditional blues” to mostly-white audiences across the increasingly ubiquitous folk, blues, and jazz festivals that had their heyday in the 1960s and 1970s. On these stages, both Hillery and Shines had to navigate their dual positions as prominent innovators of the blues and examples of its history–and the politics of traditional music festivals were anything but straightforward. At best, a concert might provide a compensated space for black artists to perform freely and in a wide range of styles, while allowing a largely white, college-age fan base to celebrate black musical innovation. At worst, it might put black music in the past-tense, separating traditional artists from the contemporary moment and denying artistic agency to the originators of a genre.

The story of Shines and Hillery’s performance is also a story of Shines and Hillery themselves. A masterful and unconventional blues musician now unjustly relegated to obscurity, Hillery began her career performing with the Georgia Sea Island Singers before striking out on her own in 1965. She had a wide repertoire that included both classic and “folk” blues songs, and grew to include some of her own protest songs; she would also spend much of the last decade of her short life integrating southern music and dance into the New York City public school curriculum. Shines was a legend in his own right, whose career in some ways parallels the conventional narrative of a twentieth-century bluesman–the soulful virtuoso shaped by his youth in the rural south, who later follows the Great Migration northward and “plugs in.” But in other ways, Shines’ trajectory was idiosyncratic. Extensive local-level performance on the Southern activist and chitlin’ circuits in the 1970s, for example, are typically excised from the famous blues man's biography, as are his brilliant critical examinations of structural racism, blues legacy, and protest during the later part of his career.[4] Both musicians were educators and activists whose clearly articulated worldviews bore a complex relationship to the folk and blues “revival” circuits, which to varying degrees positioned black artists both as exotic “others” and subjects of empathetic relatability.

Participants, fans, and music critics alike[5] tend to reflect positively on the blues and folk “revivals” of the 1960s and the 1970s. The reemergence of blues music as a commercially viable genre, the elevation of musicians like Buddy Guy and B.B. King into semi-mythic guitar gods in the world of rock and roll, and the transformation of the blues into a major international export–all of these trends reflected and enhanced the music’s growing popularity and credibility among young white audiences, and provided black blues artists with fans, stature, and work. But the surging interest in blues music wasn’t limited to the commercial realm; at the time, some progressive activist groups were beginning to use the emotional content of blues performance as part of a broader moralizing project that often ended up prioritizing cultural enlightenment over the fight for equal rights and conditions.[6]

In examining the biographies of Johnny Shines and Mable Hillery in the context of their own protest and pedagogy, this essay works to understand “traditional” blues performance–its power as an educational tool, its limitations as a vessel of political speech, the changing nature of its audience–at this time of renewed interest. We aim, also, to celebrate the political risks these two artists took alongside and against the intersecting tides of the southern activist circuits, various civil rights organizations, and the blues and folk “revivals.”

2

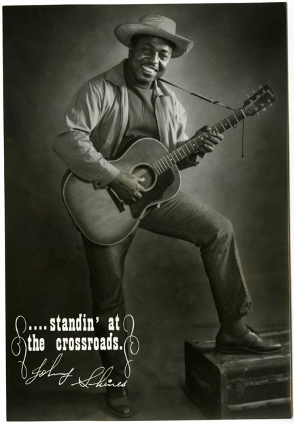

Johnny Shines provided this promotional photo to the Miami Blues Festival organizers

Born on April 26, 1915 in Frayser, Tennessee, a small farming community outside Memphis, Johnny Shines grew up between the pull of the Baptist church and the sound of the blues.[7] Though Shines came of age listening to his mother play church songs on the guitar, as a teenager he found himself spending countless hours at the local juke house and in front of the phonograph, soaking up the music of Barbecue Bob, Blind Blake, Charley Patton, and the young Howlin’ Wolf. Shines quickly learned how to play the guitar, and by the time he was twenty he was a full-time musician, traveling the country with none other than Robert Johnson. Their association ended in 1937, just a year before Johnson’s death and well before the posthumous rediscovery of Johnson’s music in the 1960s. Nevertheless, Shines, along with Johnson’s stepson Robert Jr. Lockwood, would both come to represent a direct and vital link to the elusive man’s life and music for subsequent generations.

After spending time in Memphis and St. Louis, Shines moved north to Chicago in 1941. While he quickly found himself embedded in the city’s fabled blues community, Shines encountered not just the new prejudices of the urban North, but a different set of expectations for his music. As he navigated his early days in Chicago, Shines played on Maxwell Street and in South Side clubs, also experimenting with electric guitar and jazz bands. Ultimately, though, his career stalled and he retired from music, working as a day laborer for nearly a decade. He would not record again until 1965, but these sessions reignited public interest in his music.[8] In 1969, he decided to move back south to Holt, Alabama, where he quickly became a presence on the regional scene, performing at juke houses, fundraisers, and other local gatherings. He was eager to bring his music to all kinds of community events; he even played once in support of the Freedom Quilting Bee, a South Alabama black-owned sewing cooperative that was one of many alternative economic models embraced by African Americans in the period.

Shines envisioned his return to the south as part of an effort to return the blues to its local community and to revitalize its roots as a protest music. As he described to Cadence magazine in the late summer of 1977, in the midst of his work on both the Southern “folk” and trans-Atlantic blues revivalist circuits:

The blues is goin’ to die unless somebody gets out there with me and helps me to bring the blues back to the attention of younger people and get them back to playing the blues. And forget about the filth, dirt and scum that people have smeared over the blues. Forget about it. Dig these blues up from under that scum and clean them up and bring them back to the public’s attention. That was why I moved back to Alabama. Go back to the south, take the blues back to the south where they began, that’s where they belong. Take them back home and let’s start out new.[9]

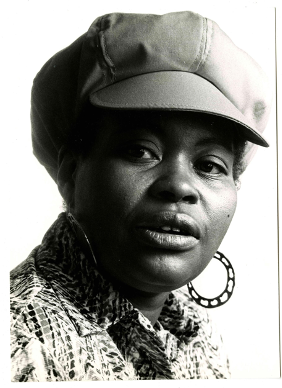

While Mable Hillery’s trajectory was different, it also pointed south. Born July 22, 1929 to sharecroppers Clarence Henderson and Mamie Zachery in LaGrange, Georgia, Hillery absorbed the folk traditions in her community, especially the songs of everyday life: blues songs, gospel hymns, and children’s rhyming games. Despite the waning popularity of classic blues singers in the Depression days of Hillery’s adolescence, her blues repertoire drew heavily on the forceful blues of female artists like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, suggesting that widely issued 78 RPM recordings and radio broadcasts of their music caught her ear at a young age.

Mable Hillery provided this promotional photo to the Miami Blues Festival organizers

Before she became professionally involved in music, Hillery married a man named Will Adams, in 1950. Throughout a decade in which she worked as a short-order cook and an ice cream vendor – while also managing to care for her six young children – music still shaped her days:

Been singin’ all my life, ever since I can remember, but I wasn’t singin’ in public. Mainly I was singin’ then in the churches and in the fields, rockin’ babies to sleep, hoein’ cotton, ploughin’ the mules, choppin’ wood, doin’ all varieties of things.[10]

In addition to her distinctive voice, the significance of song in her daily life made her particularly compelling to folklorist Alan Lomax. It was Lomax who introduced Hillery to the Georgia Sea Island Singers in 1960, a year before she formally joined the group as a contralto. A multi-generational group active since the 1920s, the Singers were dedicated to preserving African American Gullah culture by performing traditional sacred and secular songs in a range of forms. Hillery was younger than most of the group, and also more liberal in her interpretation and presentation of African American “folk” culture. The folklorist Bess Hawes described Hillery’s tendency, for instance, to cross her feet in performance of a sacred “shout”–a gesture whose perceived sinfulness deviates from the song’s sanctified content and demonstrates Hillery’s willingness to buck tradition even within “traditional” musical frameworks.[11]

A full-time member of the Singers until 1965 and an occasional participant through the late 1960s, Hillery worked the college circuit of campuses, festivals, coffeehouses, and television with the group, which was notably featured in 1964 in the Sing for Freedom Workshop in Atlanta, Georgia, sponsored by the Highlander Folk School (a locale for integrated civil rights meetings in Tennessee), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (whose first president was Martin Luther King, Jr.), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (whose push for black agency was foundational to the Civil Rights Movement). The following year, in the wake of Malcolm X’s assassination, the marches in Selma, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Vietnam War, Lomax had invited the singers to a Newport preview concert in New York City’s Central Park. Lomax’s views overlapped with those of many activists, who believed that emphasizing shared cultural traditions would bring the struggles of southern African Americans to people of different backgrounds. This would have conformed to the expectations of the burgeoning young folk audience, who came of age during what Grace Hale has characterized as a period in which emotional, not historical, connection incited an increased interest in folk music. Exalting the outsider status they saw in often black and always southern musicians, revivalists “found” themselves “in materials they could discover and control and fix in place and time.”[12]

At some point after Shines moved “back to the south” or “back home,” he crossed paths with Mable Hillery. The circumstances of their introduction are unclear, but they most likely met in the context of the Southern Folklife Cultural Revival Project (SFCRP), which was founded in 1966 by scholar-singer-songwriter-activists Bernice Johnson Reagon (an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and its auxiliary, the Freedom Singers) and Anne Romaine (who was also working with the Southern Student Organizing Committee, the leading progressive organization of young white activists in the South at that time). The SFCRP was an integrated organization that arranged for black and white traditional musicians[13] to tour together across the South. Like Lomax’s efforts on the “folk” circuit, the SFCRP pitted folk revivalism against visions of standard middle class conservatism and racism in concerts, festivals, workshops, and other outreach programs. The Project emphasized the kind of local, grassroots activism that encourages community ownership, and was distinct from Lomax’s more voyeuristic project of constructing a vision of southern authenticity to a Northern audience. In their own words, the project was “concerned that the educational institutions of the south utilize their own resources in the learning experience.”[14]

The SFCRP’s tours attempted to sustain the values of the Civil Rights Movement by dramatizing the essential regional and class connection between black and white Southerners through folk traditions and, primarily, folk music. Extant recordings of the SFCRP’s Folk Festival, for example, preserve Anne Romaine’s performance of a white cotton mill protest song just before Shines’ performance of the blues. In a clear assertion of a mutual economic plight--particularly when “the programs stress the relationship of that music to the cultural roots of the area and the political and economic history of the area,” according to a document written by Romaine--black and white musicians were meant to perform the solidarity that Romaine envisioned.[15]

3

In its fervent desire for unity,[16] however, the SFCRP risked obscuring some of the specificities of black experience that Shines in particular clearly asserted, like the legacy of forced migration and slavery. A case in point is a Southern Folklife Festival show in Atlanta on Friday April 13, 1973, in which Shines offered some sharp observations on the origins of American music. While riffing on his guitar to the tunes of “4 O’Clock Blues” and “Nobody’s Fault But Mine,” Shines spoke at length about the “coon song”[17]–a kind of minstrel song whose overt racism is complicated by its performance, often, by black musicians:

And thank goodness you know now, these same coon songs were born out of the bowel of the black man. Thank goodness you know now that all of your American music comes right out of these coon songs. Every other kind of music was imported. The songs of Wales. The songs of Ireland. The Spanish tunes--we're not Spanish, we're Americans. We are the backbone of the American music, black people's songs.[18]

He would echo this sentiment at least once in his 1978 interview with Cadence magazine:

The Irish brought their music, the Polish brought their music, the Jewish brought their music, the Swedish brought their music, the Germans brought their music, the blacks brought soul. That’s a hell of a difference.[19]

In a list that reflects both his time on the European tour circuit and his imbrication in the “folk revival,” Shines emphasizes the “imported,” “brought” quality of certain kinds of music in contrast to “black people’s songs.” Where folk songs are movable (and hence, adaptable), black “soul” is an animus, foundational to the American music that’s built upon it. The “backbone” and “bowel” that Shines invokes might be the pride and refuse of American history–and they both might apply to the “coon song,” a genre with which black performers, scholars, and listeners have had to grapple with as the base, in both senses, of black American recorded performance.[20] In his assertion that coon songs–which often used belittling caricatures of black laziness, subservience, and ineptitude to entertain white audiences–are an essential part of the DNA of black music in America, Shines stakes a claim to "all of your American music," in all its breadth and complexity. "Thank goodness" these coon songs were ours, he says–issuing a subtle challenge to an audience that likely would have been quick to condemn historical minstrelsy.

At other points, Shines did endorse a definition of the blues that diminished the significance of its origins in African American experience.[21] Flexibility was required of an artist who played both along the Chitlin’ Circuit (to a primarily black audience) and to the SFCRP’s revivalist stages in the American south as well as the trans-Atlantic and college circuits of the “blues revival.” As the blues traveled the world as a cultural export, it was subject to forces that privileged the performance of emotionally transcendent content over the blues’ specific historical context. Neither the blues revival nor the more overtly political activism of the SFCRP were immune to this kind of sentimentalizing; their success depended, in part, on making traditional music emotionally relevant to a new audience. As active performers in these spheres, Hillery and Shines rarely controlled the entire circumstances of their performances, and they were constantly adapting to new situations and audiences. These abilities were tools of the African American experience, particularly in the South, developed through a lifetime of knowing that reading a situation wrong could have dire consequences.

While Hillery’s on-stage performances were typically more coded than Shines’, some of her songs are drastically more explicit, speaking to the specific experience of being a black musician in white spaces. While she did pen a protest song that was very legible to the folk revival–the unrecorded “When Bombs Are Flying,” described in a 1967 Melody Maker article as an anti-war song inspired by her son being drafted to fight in Vietnam[22]–Mable Hillery’s only full-length solo recording explicitly foregrounded black experience. Released on the British label XTRA and issued in Germany under Vogue, It’s So Hard To Be a N***** [23] found no takers in the United States, perhaps because of its titular song.[24] The song grew out of a refrain Hillery had heard her uncle singing in the fields after he had been jailed in Atlanta during her youth, although it had roots that stretched at least as far back as 1911.[25] Hillery’s interpretation gained new resonance in an age of growing political disaffection, voiced here from a southern African American community. In one verse, Hillery sings, “When the police he ride from door to door / and he pick up the n*****s and let the white man go / that’s why it’s so hard to be a n***** / anywhere in Georgia.”

In a rare moment of reflection from her scant personal testimony, Hillery connected the It’s So Hard To Be a N***** LP to the more coded musical expression of her childhood:

I wasn’t old enough to realise the peoples was singing to relieve their anger, or on account of being frustrated, and sometimes from being happy. Singing a song would mean the world to them, because that was the only way they could talk back to the man was in the song. They would sing to the mule or to themselves, and they would beat the man by singing a song.[26]

Hillery’s sense of the nature of protest music was clearly not limited to the lyrical content of particular songs; rather, she saw the very assertion of complex humanity–the stew of anger, frustration, or joy–as itself an act of protest, a way to “beat the man” in conditions of subjugation. But the words of “It’s So Hard To Be a N*****” are entirely forthright. With its candid description of an experience of racism, this was one song that wore its grievances on its sleeve, a song that her white audiences couldn’t sing along to. We might also note that “It’s So Hard To Be a N*****” gained an increased resonance just as the Black Power movement was taking shape. While Hillery’s most meaningful associations were with organizers in the Civil Rights Movement, the claims that Black Power laid against capitalism and towards black political autonomy very much in the water as an arm of the Civil Rights Movement since at least the 1950s; Hillery’s song, while its inspiration was decades-old, seems to tap into some of this radical ethos.

While she would occasionally demur from singing material that could be deemed controversial or subversive,[27] Mable Hillery’s musical activity was increasingly linked to political and social causes throughout the late 1960s and 1970s. In 1969, for instance, she agreed to the inclusion of her song “He Was More Than a Friend of Mine” on the 1969 Italian LP L'America della contestazione, which featured radical political groups from Black Power to Maoism to Gueverra sympathizers to yippies, alongside white blues singer and activist Barbara Dane and the Reverend Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick (co-founder of the Louisiana-based Deacons for Self-Defense and Justice, an African American self-defense organization chartered in 1964 that inspired the militancy of the Black Panthers). In 1971, she toured alongside Dane at a festival in Turin, Italy organized by the communist newspaper L’Unita. She would also perform at the 1974 Puerto Rican Solidarity Day program at Madison Square Garden, and in a 1975 tour of prisons, reform schools, and retirement communities in Louisiana.

Towards the end of her life, Hillery brought her song-centered pedagogy into urban public school curriculum. Working primarily at P.S. 76 on 144th Street in Harlem, Hillery created integrated programs of southern music and dance. Working with the Interdependent Learning Model’s Follow-Through Program at the City University of New York from 1968-1976, she also spent this time organizing cultural programming for six schools in Atlanta, hosting recitals of children’s “play songs” in her position as a teacher at Bank Street College of Education in New York, and consulting for the New York City Head Start Program for free childhood development activities and educational programs. In line with her work at the SFCRP, she received a grant from the Newport Folk Foundation to pursue her project “to preserve pride in the Black heritage among those who are still part of it” through her public education work.

Johnny Shines, on the other hand, mostly taught from the stage. Committed to educating black southerners about their histories of resistance, Shines believed the blues to be at the heart of black protest. In performances of creative self-fashioning, Shines performed this protest music while also staging its explanation. During his Cadence interview, he sources his motivations in a revelation:

When I learned that black people in America were being taught to dislike themselves, that’s when I wised up to the fact that somewhere down the line I had a meaning. And someone was thriving on our dislike of ourselves and our lack of self respect.[28]

While Shines is literally addressing the primarily-white readership of the magazine, he also expresses his ontological recognition as a depth and complexity of purpose that is in stark opposition to a social structure constructed to thrive off of black suffering.

Shines sees this “lack of self respect” manifested in the declining interest in the blues amongst African American youth–which was in some measure a product of the civil rights atmosphere of the 1960s and 1970s, in which much more overt assertions of black agency and power (Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” in 1967, for example, or James Brown’s “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud” the year following) could be heard on the popular airwaves set to the more modern sound of funk and soul. Seen as the music of their parents’ generation, the blues came to represent degradation and hardship rather than protest and hope. Back in Atlanta in 1973, Shines leaves this impression on the Folk Festival stage:

Lots of people think that the blues is the most dirtiest thing in the world. That the blues is filthy, that you shouldn't sing the blues. And you can't blame them for thinking that because they have been taught. Well I'm saying the blues ain't dirty or filthy. But they wasn't told exactly about the blues, they was told about the black people's slums as a whole, and slavery time when they were singing about the conditions that they were living in, and the happenings, the state of being at that time.[29]

It is in this context that Shines introduces his project to strip the blues of this false inheritance and reassert what it truly is: a protest music with continued resonance in the politics of the 1970s. Blues, within this framework, becomes not the cause of evil but the antidote. Shines’ explanation is worth reproducing in full.

And they would sing about these things. And they had to be changed, these things had to be changed because too many people were listening to what they were singing about, and they were getting too many people stirred up about it, especially the North. Because these people, they didn't really know how to write music, to set music down on paper or set words down on paper. They sang about the things that happened to them every day. Every day happening. And after all, when you do this and play a little music to it, somebody's gonna listen. For instance, you say 'last night my house burned up ten of my children, my wife,' you understand and see what I mean–and I could walk up to you today, you're fixing to catch the bus to go to work, and say 'look, my house burned up last night and burned up ten of my children' and you say 'yeah, I listened to you but I gotta get on my bus now, I gotta go.' But, I can take the same words and set music to it, and you'd pay the next night to hear it. These people were singing these songs nationally and somebody was listening. And somebody began to getting disturbed. And somebody began to talk about these things.[30]

Shines initially locates blues protest in the time of slavery–“they sang,” “these people were singing”–but he shifts his perspective to the contemporary. That “every day happening” is both the commonplace horror of slavery and the modern setting of the hypothetical housefire and the bus to work. Shines interpellates both circumstances into a personal, one-on-one conversation: “I can take the same words and set music to it, and you’d pay the next night to hear it.” In his words, the effects of slavery’s “every day” are alive in the present, and one of the few ways to make people understand this reality is to give it a melody. Collapsing past and present abominations through song, his conceptualization of blues performance is at once an affirmation of the music’s power to spur political discussion, an explanation of the structural continuity of racist social systems and their effects on black lives, and a celebration of the everyday put to song.

In a 1967 interview with Hedy West, Hillery tread similar ground as she parsed the animating forces that drove her musical life. What she says echoes Shines’ own sense of “thankfulness” for the rich and contradictory history of black music; in the blues’ history, as much as in its words and melodies, Hillery finds solace, grounding, and direction:

So I don’t know if they are the devil’s songs or not, but in my mind they are not. I continue to sing them, because I don’t think no song is bad. And I continue to dance. It is part of me, and I have never forgot it. Kids now is sometimes ashamed of thing connected with the past, because they want to get away from the past. It was wrong for such a thing as slavery to be, but it’s nothing nobody can or should forget. I think if I should try and forget the songs that I sung, and the dances that I learned as a child coming up, I wouldn’t know who I was, and I wouldn’t know which way I was going, and I don’t want that to happen to me.[31]

4

By 1975, both Hillery and Shines had performed throughout the US and across the Atlantic, ending up almost incidentally in Miami. Even though, as Jim Fishel noted, the Miami Blues Festival “wasn’t a classroom,” there was a studied and almost scholarly aspect to Shines’ and Hillery’s performance: the pair presented their songs with ease, clarity, commitment to form, and magnetic personality in what may be the only surviving concert-length example of their performance as a duo.[32]

Rather than performing overtly political music, the songs that Shines and Hillery play are primarily drawn from a repertoire of classic blues songs first performed by women. The songs are filtered through Hillery’s musical and intellectual voice, and the effect is a hybrid of the past and present. Hillery said it best herself: “Take some of your verses and add some of their verses.”[33]

Shines’ contribution is exclusively instrumental, but his deft guitar work demonstrates his Delta roots, with tasteful runs that spur Hillery onwards. In a variation on the great “empress of the blues” Bessie Smith’s “Young Woman’s Blues,” Hillery refuses to settle down, telling her audience instead, “I’m [gonna] drink my moonshine liquor and I’m gonna run all you men wild.” In another variation that sounds uncannily close to Memphis Minnie, Hillery embraces her sexuality in “Bumble Bee Blues,” reveling in the double entendre of asking her man to “sting me some more.” And even in what should be a vulnerable moment in “Come Back Baby,” Hillery is alternately stoic and confident:

Said you were leaving this morning

Ain’t gonna scream and scream

I’m gonna take it like a woman and I’ll tell you the reason why

You’ll be back baby and we’ll talk it over one more time

Where Hillery’s commentary on race is muted by comparison to some of her other work, her assertion of her own sexuality as a black female performer is more conspicuous here; this, in itself, was as daring and political an act of self-presentation as it had been when Hillery’s forebears had done the same thing in the 1920s and 30s.

The Miami Blues Festival found these two extraordinary artists in what for them must have been a fairly ordinary setting: the college circuit, playing traditional blues for a mostly-white audience. With both artists long-deceased and hardly any archive of the festival to speak of, the trials and triumphs of the festival are difficult to access. But what survives in this performance, and in others like it, is evidence of dynamic musical and political expression–expression that attests to the trials of black artists who attempted to communicate nuanced personal and political views on revivalist circuits. Both Shines and Hillery adapted their work into and against the structures that, for better or worse, have given us a limited but enduring record of their music, their lives, and their thought.

Footnotes

[1] In full disclosure Jim Fishel is the father of co-author Parker Fishel, as well as a co-producer of the author’s LP reissue of Mable Hillery and Johnny Shines’ 1975 Miami Blues Festival performance.

[2] Jim Fishel, telephone interview by Sophie Abramowitz November 27, 2017, audio.

[3] Recordings from all four festivals, housed in Jim Fishel’s personal reel-to-reel collection, include sets by Hound Dog Taylor, Roosevelt Sykes, Jimmy Dawkins, Carey Bell, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Johnny Shines, Dr. Ross, J.B. Hutto, Mance Lipscomb, Otis Rush, Robert Pete Williams, Houston Stackhouse, Big Walter Horton, Luther Allison, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Son Seals, Jimmie Walker, Eddie Baccus, Koko Taylor, and Mable Hillery, among others.

[4]While Shines’ work in this regard is mentioned in various biographical dictionaries of the blues, we have found neither an extended interview nor a sustained analysis of his activism on local, predominantly southern, stages.

[5] See for example Steve Cushing, Pioneers of the Blues Revival (Indiana: University of Illinois Press, 2014); Bob Groom, The Blues Revival (Worthing: Littlehampton Book Services, 1971); John Milward, Crossroads: How The Blues Shaped Rock and Roll (And Rock And Roll Saved The Blues) (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2013);and Robert Cantwell’s When We Were Good, below.

[6] For a more extended discussion of white folk music listeners’ sentimental identification with romanticized ideas of blackness and “southern-ness,” see Grace Hale, Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell In Love With Rebellion in Postwar America (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2014) and Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000). Discussion of the racial and class disjunction between white revivalists and the subjects of their protest songs can be found in Ronald D. Cohen’s Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940-1970 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002). The latter and Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997) give extended surveys (if different periodizations) of the movement.

[7] Biographical information is sourced primarily from: Johnny Shines, “Johnny Shines: The Complete 1989 Living Blues Interview,” interview by Jas Obrecht, January 23, 1989, transcript, http://jasobrecht.com/johnny-shines-complete-living-blues-interview/.

[8] These sessions would be part of the classic Vanguard compilation Chicago/Blues/Today! (Chicago: Vanguard VRS 9218, 1965).

[9] Johnny Shines, “Johnny Shines: Interview,” interview by Bob Rusch and Mike Joyce, Cadence: The American Review of Jazz & Blues 3, No. 10, February 1978, 13.

[10] Jean Aitchison, “Mable - The Blues Singing Grandmother,” Melody Maker, October 28, 1967, 22.

[11] Peter Stone, “Mable Hillery,” Association for Cultural Equity, accessed November 2017, http://www.culturalequity.org/alanlomax/ce_alanlomax_profile_mable_hillery.php.

[12] Grace Hale, Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell In Love With Rebellion in Postwar America (Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2014) 101.

[13] The organization brought together a rotating group of musicians from various backgrounds and traditions, including Dewey Balfa, Furry Lewis, Dock Boggs, Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard, Reverend Pearly Brown, Mike Seeger, Shines, Hillery, and Romaine herself. To corroborate, various Folk festival programs are available in the Anne Romaine Papers, 1935-1995, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20304, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[14] ‘Music and History’ Public School Programs Pamphlet, Subseries 2.4, Box 11, Folder 113, SFCRP Publicity (1 of 3), Anne Romaine Papers, 1935-1995, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20304, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[15] Form 1023 Rider to Pt. III-1 of Application for Certificate of Authority for Not For Profit, Subseries 2.4, Box 11, Folder 109, SFCRP Corporate Documents, Anne Romaine Papers, 1935-1995, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20304, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[16] In Nation of Outsiders, Grace Hale makes a similar point about the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)’s Southern School, pointing to a trend in radical groups

[17] In the recordings of his performance, Shines actually seems to alternate his pronunciation between “coon,” “coin,” and “corn;” because he is discussing blues history, we assume he is referring to the “coon song,” a genre of racist, stereotyped pastiches of black performance that was popular during the turn of the twentieth century.

[18] SFC Audio Open Reel 5918: Southern Folk Festival, Great Southeast Music Hall, Atlanta, Ga., April 1973.: Side 2, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[19] Johnny Shines, “Johnny Shines: Interview,” interview by Bob Rusch and Mike Joyce, Cadence: The American Review of Jazz & Blues 3, No. 10, February 1978, 13.

[20] See in particular Houston A. Baker, Jr., Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987). The relationship that Shines draws between black physicality and blues music is also reminiscent of that of a theoretical predecessor, Amiri Baraka, who wrote that blues “was an American sound, something indigenous to a certain kind of cultural existence in this country.” Amiri Baraka, Blues People (New York: Harper Perennial, 1963), 79.

[21] For example, during his 1989 interview for Living Blues (see footnote 6), a magazine with a broad-based primarily-white readership, Shines once claimed: “You see, blues don’t have no race. “Blues don’t have no level. The blues is just like death. Everybody is going to have the blues.”

[22] Jean Aitchison, “Mable - The Blues Singing Grandmother,” Melody Maker, October 28, 1967, 22.

[23] We have chosen to censor the word in question; as three white writers, we feel that using this language in our retelling of Hillery's story substantively changes the meaning that the word would have had when it came from her. We hope that our decision in no way diminishes Hillery’s agency and courage in using the word to make important social and political points.

[24] In a letter to Hillery from Anne Romaine, she reports that the record’s co-producer Joe Lustig explored options including Bernard Stollman’s ESP-Disk imprint, home of avant-garde jazz and folk artists like Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, and The Fugs. Series 1. Artist Files, 1966-1989, Folder 61: Mable Hillery, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[25] Originally collected by sociologist Howard L. Odum in 1911, it was first published in a 1928 paper co-written with Guy B. Johnson, “The Negro and His Songs: A Study of Typical Negro Songs in the South.”

[26] Hedy West, liner notes, It’s So Hard To Be A N***** (XTRA 1063), 1968.

[27] In a circa 1967 letter from Hillery to Anne Romaine, Hillery mentions being in consideration for a State Department-funded tour abroad, a tool of cultural diplomacy that had assertions of the blues’ universality at its core. For fear of jeopardizing the opportunity, she initially abjured from singing peace and Civil Rights songs at the 1968 SFCRP Folk Festival. Eventually she agreed, with the promise that it would not be publicized. Series 1. Artist Files, 1966-1989, Folder 61: Mable Hillery, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[28] Johnny Shines, “Johnny Shines: Interview,” interview by Bob Rusch and Mike Joyce, Cadence: The American Review of Jazz & Blues 3, No. 10, February 1978, 14

[29] SFC Audio Open Reel 5918: Southern Folk Festival, Great Southeast Music Hall, Atlanta, Ga., April 1973.: Side 2, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[30] SFC Audio Open Reel 5918: Southern Folk Festival, Great Southeast Music Hall, Atlanta, Ga., April 1973.: Side 2, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[31] Hedy West, liner notes, It’s So Hard To Be A N***** (XTRA 1063), 1968.

[32] The first mention of Shines and Hillery performing together appears in a letter that Anne Romaine wrote to Shines on January 31, 1973, thanking him for backing up Hillery during a recent performance in Macon, Georgia. Shines and Hillery shared a stage twice in 1973–once for the SFCRP’s Folk Festival (from which much of the material for this essay is drawn), and once in an SFCRP-sponsored performance in Dallas, Texas; and again in the early part of 1974. Series 1. Artist Files, 1966-1989, Folder 61: Mable Hillery, in the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[33] Hedy West, ibid.

Bibliography

Aitchison, Jean. “Mable - The Blues Singing Grandmother.” Melody Maker, October 28, 1967.

Baggelaar, Kristen and Donald Milton. “The Georgia Sea Island Singers.” In Folk Music: More Than A Song, 143-144. New York: Crowell, 1976.

Baker Jr., Houston A. Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1987.

Baraka, Amiri. Blues People. New York: Harper Perennial, 1963.

Cantwell, Robert. When We Were Good: The Folk Revival. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1997.

Carmichael, Stokley. “Power and Racism: What We Want.” The Black Scholar 27.¾ (1966).

Cohen, Ronald D. Rainbow Quest: The Folk Music Revival and American Society, 1940-197. Amherst: Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2002.

Cushing, Steve. Pioneers of the Blues Revival. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 2014.

Earl, John. “A Lifetime in the Blues.” Blues World 46/49 (1973): 12-13, 20-21.

Filene, Benjamin. Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Fishel, Jim. Telephone Interview. Interview by Sophie Abramowitz. New York: November 27, 2017. Audio.

Form 1023 Rider to Pt. III-1 of Application for Certificate of Authority for Not For Profit. Subseries 2.4, Box 11, Folder 109, SFCRP Corporate Documents, Anne Romaine Papers, 1935-1995. In the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20304, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Groom, Bob. The Blues Revival. London: Studio Vista, 1971.

Guralnick, Peter. “Johnny Shines: On the Road Again.” Feel Like Going Home: Portrait in Blues and Rock and Roll. New York: Back Bay Books, 1999.

Hale, Grace. Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell In Love With Rebellion in Postwar America. Cambridge: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Harris, Sheldon. “Shines, John Lee Ned ‘Johnny.’” In Blues Who’s Who: A Biographical Dictionary of Blues Singers, 457-58. New York: Da Capo, 1982.

Harris, Sheldon. “Hillery, Mable.’” In Blues Who’s Who: A Biographical Dictionary of Blues Singers, 230-31. New York: Da Capo, 1982.

“Hillery, Mable.” The Black Perspective In Music 4, No. 3 (Autumn 1976): 345-46.

Komara, Edward. “Hillery, Mable.” In Encyclopedia of the Blues, Volume 1: A-J, edited by Edward Komara, 432. New York: Routledge, 2006.

“Mable Hillery.” Living Blues 28 (July/August 1976): 6.

“Mable Hillery, Sang Spirituals.” New York Times, May 1, 1976.

Milward, John. Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock ‘n’ Roll (And Rock Saved the Blues). Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2014.

‘Music and History’ Public School Programs Pamphlet. Subseries 2.4, Box 11, Folder 113, SFCRP Publicity (1 of 3), Anne Romaine Papers, 1935-1995. In the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20304, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

SFC Audio Open Reel 5918: Southern Folk Festival, Great Southeast Music Hall, Atlanta, Ga., April 1973.: Side 2. In the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Series 1. Artist Files, 1966-1989, Folder 61: Mable Hillery. In the Southern Folk Cultural Revival Project Collection 20004, Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Shines, Johnny. “Johnny Shines: The Complete 1989 Living Blues Interview.” Interview by Jas Obrecht. January 23, 1989. Transcript. http://jasobrecht.com/johnny-shines-complete-living-blues-interview/.

Southern, Eileen. “Hillery, Mable.” In Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians, 182. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Southern, Eileen. “Shines, Johnny.” In Biographical Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians, 336-37. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Shines, Johnny. “Johnny Shines: Interview.” Interview by Bob Rusch and Mike Joyce. Cadence: The American Review of Jazz & Blues 3, No. 10 (February 1978): 3-15.

Stone, Peter. “Mable Hillery.” Association for Cultural Equity. Accessed November 2017. http://www.culturalequity.org/alanlomax/ce_alanlomax_profile_mable_hillery.php.

Tomko, Gene. “Johnny Shines.” In Encyclopedia of the Blues, Volume 2: K-Z, edited by Edward Komara, 877-78. New York: Routledge, 2006.

West, Hedy. Liner notes. It’s So Hard To Be A N*****. XTRA 1063, 1968. LP

West, Hedy. “Mable Hillery, 1929–1976.” Sing Out! 25/1 (May/June 1976): 38.

Wirz, Stefan. “Johnny Shines Discography.” American Music. Last modified July 24, 2017. https://www.wirz.de/music/shinefrm.htm.

Wirz, Stefan. “Mable Hillery Discography.” American Music. Last modified May 17, 2017. https://www.wirz.de/music/hillefrm.htm.

Wise, Steve. “Southern Folk Festival.” Great Speckled Bird, April 23, 1973.