Willie Lynch, Drummer – Biography and Discography, 1899-1930

Melissa Jones

William Hyland Lynch was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, August 13, 1899. His father, Lucene, was born in Liberia and his occupation is listed as “cook.” Willie’s mother, Gertrude (Smith) was born in Massachusetts (Source: William Hyland Lynch birth certificate). By the 1910 census, Gertrude is indicated as “head” of house and her occupation is “wash woman.” There are two sons and two daughters residing at the residence (Willie being the youngest) with her husband unlisted.

No information is yet available on Willie’s childhood, his education, or musical acumen. Nothing surfaces until the 1920 census.

It’s here the story takes an astonishing musical turn. Milton Senior, multi-reed instrumentalist and primary member of the Synco Septette and McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, is Willie’s roommate! Residing at 705 Selby Street, Alliance, Ohio (northeast of Canton, Ohio), both are listed as “musicians working in a theater.”

It’s unknown how, when, or with whom Willie arrives in New York City, but it is certain he arrives in the Big Apple by 1924.

Billy Butler was born in New York and comes from an accomplished musical family. Taught by his music teacher father, Billy began playing violin in the family band. His ability was quickly recognized and, as a youngster, he received a scholarship to study with David Mannes, concertmaster with the New York Symphony (1898-1912) and founder of the Mannes School of Music. By 1924, Billy had become smitten by jazz, relinquished his violin for a saxophone and started his own jazz band – Billy Butler’s Band. The band would evolve, being renamed several times, but with a core group remaining until the band’s demise. The original members include: Raymon Hernandez (ts), James Reevy (tb), Gilbert Paris, Demas Dean (tpt), Leroy Tibbs (pn), Englemar Crummel (sax), Willie Lynch (dr), Jimmy Green (bj), Chink Johnson (tuba), and Billy Butler (leader/sax/violin) (Source: Demas Dean).

Billy Butler’s Band soon established itself as a contender in the 1920’s Harlem jazz scene with an engagement at Harlem’s Nest Club. Trumpeter Demas Dean noted the success of the band, adding, “Butler rehearsed us well.” Demas also remembered their repertoire included “Hymn to the Sun,” “Scarf Dance,” “Oriental Fantasy,” and “Tannhauser.” “We would go to work at 10 o’clock and many a morning, we’d be coming out at six or seven,” recalled Dean.

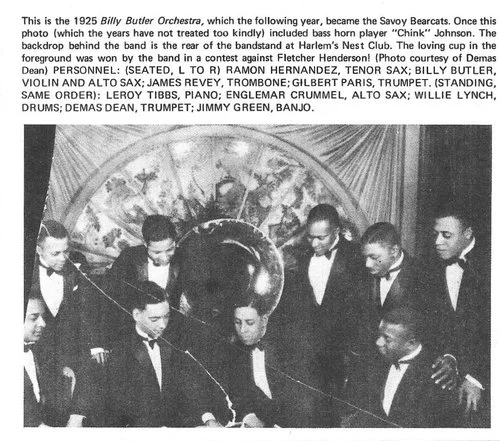

The 1925 photograph featured above shows Billy Butler’s Band at the Nest Club. The band is staring downward at a recently acquired trophy, won in a hard fought battle-of-the-bands with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra. The musicians are those listed above. Willie Lynch is seated, far right (Demas Dean Collection). Coupled with the Nest Club engagement, the band was performing throughout the New York City metropolitan region. The Pittsburgh Courier covered engagements in New Jersey and the Hartford Courant advertised multiple appearances at Le Bal Tabarin, a stylish Connecticut venue for dining and dancing. The band was gaining exposure and developing an audience, but more importantly, they were honing the musical skills necessary for a contender within Harlem’s competitive jazz scene.

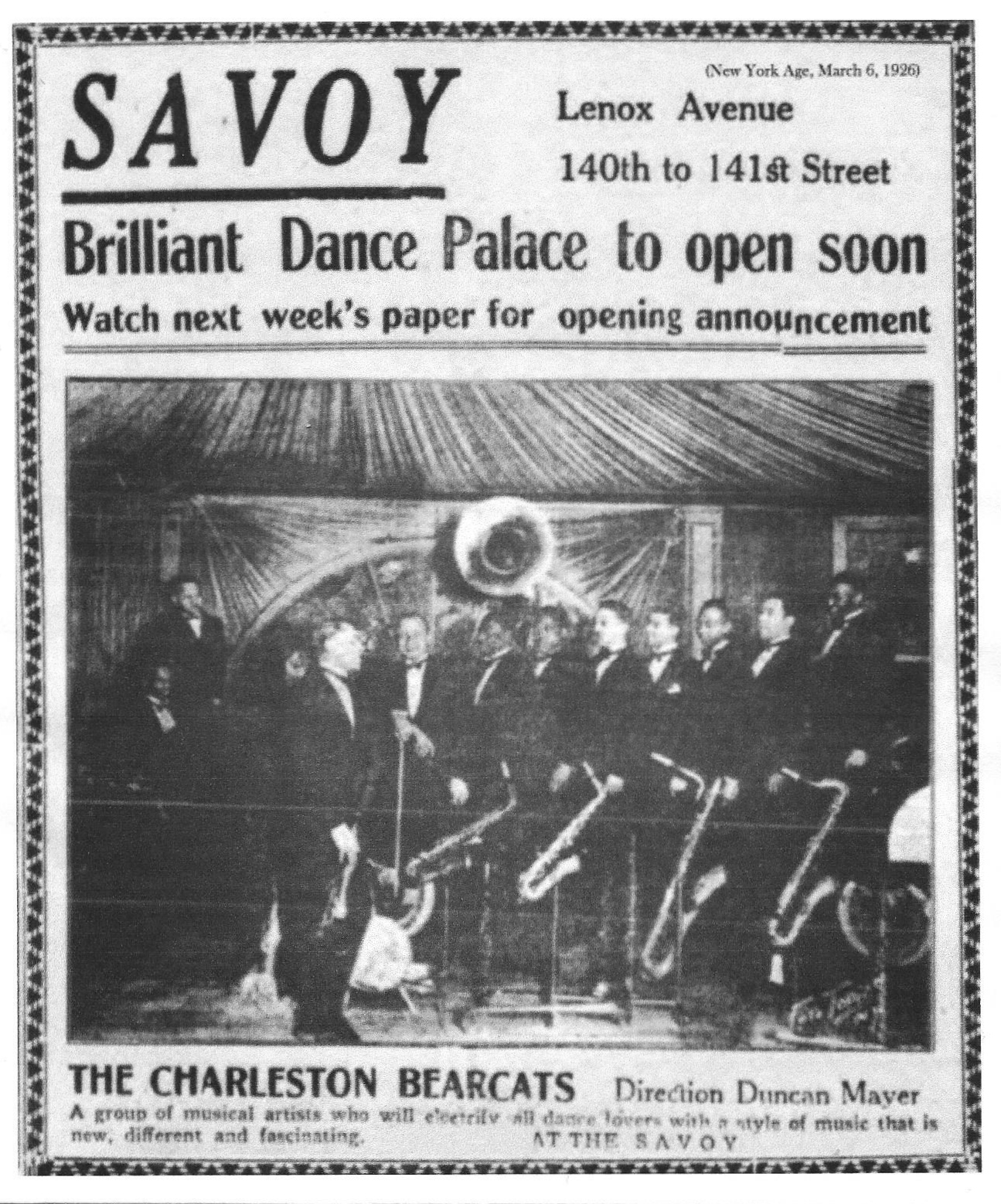

In 1926, the band assumed a momentary name change, The Charleston Bearcats and took on new leadership in Duncan Mayers. It’s unclear as to the reason. Demas Dean asserts the band was never from Charleston and Mayers was merely a contractor for the band. What is clear, however, is the band’s next engagement.

In 1923, New York found itself the epicenter of the “ballroom wars.” Walter C. Allen’s account in Hendersonia describes the phenomenon, providing extensive data and a vivid picture of the competition among ballroom owners. As the number of venues multiplied, size and elegance became de rigueur.

Investors Charles Galeski, Murray Gale, Larry Spier and I. Jay Fagan believed their newest undertaking would provide their dance clientele the ultimate ballroom experience. They, also, believed their venture would make money. Little did they realize that their 1926 enterprise would, some 90 years later, remain the icon of dance ballrooms, evoking romantic visions of dancing patrons launching their partners to unimaginable heights, while dancing to the music of iconic Jazz bands. The legendary Savoy Ballroom was about to open.

Amid intensive hype and hoopla, the Savoy opened on March 12, 1926. Two bands were hired for the occasion, Fess Williams and his Royal Flush Orchestra and Duncan Mayers’ Charleston Bearcats. Almost immediately, the Charleston Bearcats changed its name to the Savoy Bearcats and replaced its nominal leader Mayers with leader/violinist Leon Abbey. Having evolved into The Savoy Bearcats, the personnel remained similar to the original band Billy Butler assembled: Gilbert Paris, Demas Dean (tpts), James Reevy (tb), Carmelo Jari (Jejo) (clt, alto, bari), Otto Mikell (clt, alto), Ramon Hernandez (clt, tenor), Leon Abbey (violin/leader), Joe Steele (p), Freddy White (bjo, guitar), Harry Edwards (tuba), Willie Lynch (dr).

The Savoy opening was a huge success. Interestingly, in an attempt to hedge his bet, investor Fagan had also hired the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, engaging the band for the first three nights from 1:00-2:00 AM. Fagan’s plan may have been unnecessary though, as attendance continued to skyrocket. Variety opined that not only was the Henderson orchestra unnecessary, it was a detriment. Referencing the house bands by number of musicians (Fess Williams, seven members, and the Bearcats, eleven members), Variety (March 31, 1926 as quoted in Hendersonia) states:

Fletcher Henderson, whose colored jazzists are the aces of the Roseland ballroom in Times Square is dragged in for comparison with his uptown contemporaries. Henderson’s jazzapation for the white man’s consumption may be properly adulterated, but for the red hot scorching jazz, that Harlem 7 and 11 team is the ultimate.

As the Bearcats popularity increased, opportunity came knocking. The band’s services, including “special attraction” appearances multiplied. Exposure to an expanding audience occurred when the band began broadcasting from the New York studios of WEAF, but ultimate success happened when the band signed a coveted recording contract with the premier recording company, Victor:

The Savoy Bearcats, directed by Leon Abbey, formerly known as the Charleston Bearcats, were honored in professional musical circles last week, when the Victor Phonograph Co. signed them up to make exclusive records for dance music. It is the first time a colored orchestra has been engaged to make records exclusively for the world’s largest phonograph company (New York Age, August 21, 1926).

By all accounts, the Bearcats had arrived.

At the conclusion of the Savoy engagement and basking in new found fame, Leon Abbey secured a contract for a South American tour, renaming the aggregation Leon Abbey’s Orchestra. As a co-operative unit, band members could decide whether or not to participate in the journey. The tour would last approximately eight months and several band members opted to remain in New York. According to Demas Dean, Abbey spent the entirety of the journey rehearsing the band and familiarizing new members with Bearcat repertoire. Performing in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Sao Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro, the band wowed highly motivatd crowds by playing the current jazz repertoire, including musician Dean’s demonstration of “the Charleston” nightly to a highly motivated dance crowd. The band returned to the Port of New York aboard the S.S. Southern Cross on October 11, 1927. The ship’s roster listed the Leon Abbey Band and members: John W. (Nat) Brown and Demas Dean (tpts), Robert Horton (trom), Joseph C. Garland, Prince Robinson and Carmelo Jejo (sax), Earl Fraser (piano), Phillip F. Blackburn (banjo), Henry Edwards (tuba), William H. Lynch (drums) and Leon A. Abbey (violin/leader).

At this point, the Billy Butler/Charleston Bearcats/Savoy Bearcats/Leon Abbey Band dissolves and should be recognized as more than a footnote in jazz history. The band, an active participant in early Harlem jazz history, opened the legendary Savoy Ballroom. The tour, throughout South America, expanded the jazz audience. Their discography reflects highly skilled musicians, playing intricate, arranged music, with flawless precision.

It’s here Charlie Holmes, through the Institute of Jazz Studies Oral Archives and encouraged by interviewer Albert Vollmer, provides invaluable information regarding the next phase of Willie Lynch’s career. Holmes highlights, not only his own unique story and professional experiences as a sideman in Harlem, but a detailed account of Willie Lynch’s next career move.

In early 1929, Harlem was riding the wave of prosperity. The entertainment industry, capitalizing on Americans leisure time and spendable income, provided numerous forms of entertainment. The “revue” – a stage show replete with dancers, comedians, and actors – presented not only a highly enjoyable form of entertainment, but a lucrative income for writers, producers, theater operators, and Willie Lynch. As a seasoned musician, Willie’s talents were easily marketable, expanding from musician-drummer to leader and contractor. Developing a reputation as “having a great band” and “being known up and down the street” (Holmes), Willie’s expertise attracted the attention of many, including jazz notables.

Duke Ellington’s Cotton Club engagement, beginning in 1927, catapulted his band into stardom. Exposure, via national radio broadcasts, heightened the band’s visibility while simultaneously defining the Cotton Club as a premier venue. An evening at the Cotton Club was memorable, combining the Cotton Club Revue, accompanied by the Ellington Orchestra, with dance music, also provided by the Ellington aggregation. It was a long night, only becoming more complicated when the band (and Revue) participated in a “special attraction engagement.” It was not uncommon for the band, following the Revue, to exit the Cotton Club, rush to another Harlem venue, perform, and return to the Cotton Club just in time for the second performance. On these occasions, Duke hired Willie Lynch’s band as his substitute (New York Age, January 26, 1929). It’s here, the story takes an interesting twist.

Long before Minton’s Playhouse became a jazz hotspot, its founder Henry Minton patrolled the streets of New York as Sergeant-At-Arms for Musicians Local 802. His duties included, “the right to attend all engagements played by members, examine their financial cards, and see that all the men engaged in the job are members of 802 or properly affiliated through a transfer card.” Complying with union regulations added an extra dimension to the workplace. It behooved the musicians to comply, as a late night visit from Sergeant-At-Arms Minton could result with a penalty. At the beginning of January 1929, Willie Lynch was contacted by Duke Ellington. Duke, in need of a substitute band, inquired of Willie’s availability. Willie indicated he and the band had a prior engagement, but Ellington continued asking Lynch if he could supply another band for the evening. Willie indicated he could, but emphasized he could not be present. Ellington agreed and the engagement was scheduled.

Sergeant-At-Arms Minton, while making the evening’s rounds, stopped by the Cotton Club. Finding Ellington’s band absent, he proceeded to card the musicians. All were “legal” except saxophonist Steve Wright, a newcomer to New York. Wright had not obtained a union transfer card. Shortly thereafter, both Willie Lynch and Steve Wright were summoned before the union hearing board. Pleading guilty, Lynch explaining his unavailability for the evening, indicated Duke told him to “do the best he could” and hired Steve Wright because “he thought he was alright.” The board, noting Lynch’s good standing in Local 802, did not issue a fine, but told Willie “to do better the next time.” Steve Wright, also pleading guilty, was fined the minimum penalty of ten dollars.

Willie Lynch, building upon his successes, continued to secure opportunities for himself and the band. In February 1930, Lynch and crew were booked into the glamorous Coconut Grove night club (NYC), situated high atop the elegant Century Theatre. The impressive location and grand architecture was dwarfed by the jazz giant who fronted Willie’s band – the incomparable Louis Armstrong (Louis - The Louis Armstrong Story by Max Jones & John Chilton). Syndicated columnist Walter Winchell covered the event, but unfortunately for jazzers, his article provides more details describing the lavish surroundings than Armstrong’s musical presence. At the close of the engagement, Chilton reports the Lynch band accompanied Armstrong on tour. This was denied by Louis’ agent, Tommy Rockwell. In an interview reported in Baltimore’s Afro-American, Rockwell insists the decision regarding bands was his alone and Willie Lynch did not accompany Armstrong on tour.

Whatever the situation, the following recording dates became the reality. The Willie Lynch Band fronted by Louis Armstrong made the following recordings:

The 1930 census reveals Willie Lynch residing at 36 West 138th Street #114, along with three additional roommates: Castor McCord, Rokel [sic*] Holmes, and Sarah Anderson. All three men are listed as “musicians working in a night club,” and Sarah is listed as “hostess working in a night club.” Castor McCord, clarinet and tenor sax, was a member of the Lynch aggregation. Interestingly, Shelton Hemphill lives in the apartment next door (#113) and would become a member of the Mills Blue Rhythm Boys. Castor McCord’s twin brother, Ted, lives around the corner and was also a member of Willie Lynch’s band. I believe “Rokel” is a misspelling of “Robert.” Robert “Bobby” Holmes played clarinet and alto sax and was a member of the Lynch band.

The summer of 1930 found Willie Lynch directing the orchestra at Harlem’s Saratoga Club. It’s unclear whether Willie Lynch’s band assumed the moniker of Saratoga Club Orchestra or if, in fact, the orchestra was a Saratoga Club Orchestra. It should also be noted, the Saratoga Club was the domain of the Luis Russell Orchestra, so clarity as to orchestra identification remains murky at best. In November of 1930, Willie returned to the stage leading the orchestra of Irvin C. Miller’s annual revue, “Brownskin Models of 1931.” Acclaiming the revue as the best of the Miller revues, a star-studded cast is cited along with a large chorus with the orchestra “under the direction of Willie Lynch” (New York Age, 11/1/1930).

Recapping Willie Lynch’s career in New York, from 1924 to mid-1930:

Drummer, Billy Butler Band/Charleston Bearcats, 1924-1926

Drummer, Savoy Bearcats, opening the Savoy Ballroom, 1926

Recorded with the Savoy Bearcats, 1926

Toured South America, increasing the jazz audience, 1927

Subbed for Duke Ellington at the Cotton Club

Lynch band fronted by Louis Armstrong, 1930

Lynch band recorded with Louis Armstrong, 1930

Willie Lynch directed orchestras for numerous Harlem revues.

By October, 1930 the economic calamity of the Great Depression was well underway. Harlem musicians were experiencing its effects with theater owners, in an attempt to curb costs, replacing musicians with “mechanical devices.” Local 802, addressing the situation, initiated an extensive ad campaign coupled with membership meetings to air grievances. With attendance resulting in overflow crowds, explanations were met with boos and jeers. Times were tough and unemployment for stage musicians was skyrocketing. “Activities of Union Musicians” reports, thirty Harlem “race” musicians, regularly employed by Harlem theaters, were now among the ranks of the “army of unemployed musicians.” Willie Lynch could not have been immune to the situation, but two fortuitous events occurred, providing employment and opportunity impossible to ignore. Within weeks, Willie Lynch’s Band would be renamed the Mills Blue Rhythm Band.

In the fall of 1930, Charles Buchanan, manager of the Savoy Ballroom, contacted Willie Lynch. Buchanan, hiring an additional band for the Savoy, asked of Willie’s availability. Lynch agreed to “get a band together.” but with one stipulation…Buchanan had to agree to his price! Reflecting with satisfaction, Charlie Holmes, altoist for the band, recounts the moment while providing a slice into the business acumen and personality of Willie Lynch:

CH: Later on, they wanted a band in the Savoy. Buchanan, manager of the Savoy, got in contact with Willie and Willie got together some musicians for him and it was Willie Lynch’s Band. That’s all I ever called it. But, ah…I just recall who else was in the band. I know Chick Webb was on the other bandstand while we were working there, but we were making more money than Chick.

AV: I see.

CH: But, ah...and…Chick was supposed to be such a big favorite up there, but we were making more money than Chick was and we were just a “put together band.” Get together, you, know. But that was because Willie held out for more money. Willie wouldn’t work for under a certain amount.

AV: Do you remember what you made?

CH: No, I mean it was over the line as far as what Chick was getting.

AV: What roughly were the wages in those days?

CH: Well, $50.00 a week, which wasn’t bad, but Willie’s band was getting more than that.

But Willie had more on his mind than a plum engagement at the Savoy. He was rehearsing the new band in preparation for Irving Mills “to take a look at” (Holmes). Willie’s band was a contender for replacing the Cab Calloway Orchestra at the Cotton Club.

Charlie Holmes could not recall the roster of entire group, but what he did remember provides food for thought and further research. He indicates Joe Steele was on piano, possibly Cass McCord on tenor and Jabbo Smith (!) on trumpet. Vollmer pursued the questioning with Holmes standing firmly on Jabbo’s presence, adding there was only one trumpet and Jabbo was there from the beginning. Holmes ends stating, “Jabbo was a real asset to the band.”

In November 1930, a new revue, “Uptown Capers” opened at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre. Advertised as a “Peppy, Beautiful, Funny Revue,” the star-studded cast of forty-five, included Sandy Burns, George Wiltshire, Amanda Randolph, The Four Singapores, Pee Wee and Eddie, Apus, Helen Stewart, and Willie Lynch’s Rhythm Aces. The production was lavish with pianist Edgar Hayes’ rendition of “Star Dust” accompanied by a cascade of falling stars becoming the show stopper. The production was a resounding success and it is here, Irving Mills hired Willie Lynch and his band “on the spot” (Holmes).

Within weeks, Willie Lynch’s Band became the property of promoter Irving Mills. The band, assuming as many names as leaders, was now under the auspices Harlem’s most powerful promoter of musical talent. For Willie Lynch, the relationship would be brief with a termination leaving many unanswered questions. Two sources, New York Age and Charlie Holmes, provide the details.

Joining the Mills Blue Rhythm Band shortly after its formation, Charlie Holmes indicated there was dissension among the group from the very beginning. Band members who only weeks earlier had been earning more money than the Chick Webb Orchestra, were now complaining about salaries. After the group’s first tour, they returned to New York, emboldened by large crowds and giddy with success. A meeting with Irving Mills was scheduled with Charlie Holmes becoming the unintended spokesman. Holmes presented the band’s grievances. “In a room so quiet you could hear a pin drop” (Holmes), Charlie Holmes became one of many Blue Rhythm casualties – he was immediately fired by Mills. It remains unclear whether Willie attended the meeting, but the power of Irving Mills had been voiced and his control understood. Willie’s future would hold no better outcome than Charlie Holmes.

Willie’s last recording date with Mills Blue Rhythm Band is July 30, 1931. By the band’s next recording session, February 25, 1932, changes have occurred including Willie’s departure. Sometime within that seven month period, Willie’s drum chair is relinquished to O’Neil Spencer with Willie’s new job description becoming one of two managers. Talk among band members surmised a group their size did not need two managers and the move could only predict an unfavorable outcome for their leader.

The Blue Rhythm Boys, an aggregation which was assembled and led by Willie Lynch for a long while, is scheduled to take Cab’s place at the Cotton Club. But Willie Lynch will not be there with them, as on a previous occasion. The B.R. Boys got engulfed by a Broadway promoter and recently, it is alleged, Willie Lynch got his walking papers – a two week’s salary payment terminated his connection with the orchestra he had formed (New York Age, January 9, 1932).

The Mills Blue Rhythm Band would continue, well into the 1930’s, but without its founder and leader Willie Lynch.

It’s here the Willie Lynch story comes to an abrupt halt. The 1940 census lists Willie Lynch residing in New York City at 1840 Seventh Avenue # 226, along with wife Marie and six year old son Arthur. Willie, the respondent, lists himself as “a musician working in an orchestra.” No death certificate has been located and the 1950 census will not become available until April 2022. In addition, author Gene Ferrett, in his excellent book Swing Out, Great Negro Dance Bands, provides a 1927 photograph of the Leon Abbey Band touring South America (pictured above). Abbey, providing musician identifications, refers to drummer Willie Lynch as “the late Willie Lynch.” The book was copyrighted in 1970.

The Willie Lynch story remains incomplete. For instance, no definitive connection could be attached to musician Bingie Madison. And one clue remains for future researchers: New York Age in a feature for the newspaper, conducted a “man-on-the-street interview,” with Harlem pedestrians being asked, “What is your pet peeve?” Willie Lynch, truck driver, is a respondent. The paper is dated August 14, 1954.

Sources: Government documents, newspaper articles, and research materials from various authors were utilized. Significant contributions from musicians Demas Dean (“The Story of Demas Dean” by Peter Carr, Storyville 72, August-September 1977) and Charlie Holmes (Institute of Jazz Studies, Jazz Oral History Project, Albert Vollmer, interviewer, 1982) provide the most comprehensive account of Lynch’s career. As primary sources, Dean’s and Holmes’ combined recollections contribute the most accurate timeline for the elusive Willie Lynch. Additional information from New York Age provided both new and corroborating support while discographical information was included from Brian Rust, Jazz Records 1897-1942, Volumes I-II.